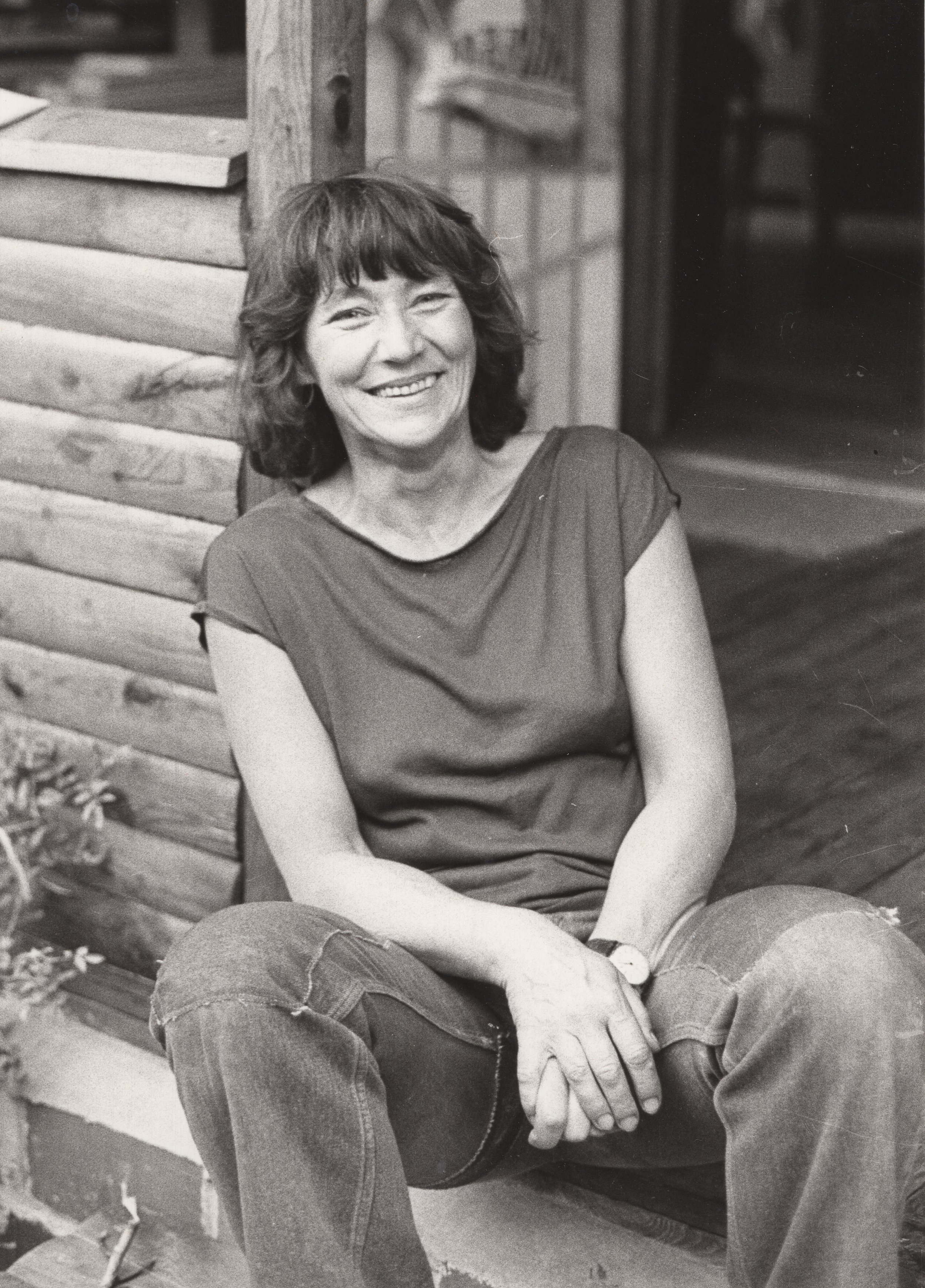

Magdalena Abakanowicz

1930-2017

Hailed the godmother of installation art, Marta Magdalena Abakanowicz Kosmowska made monumental yet vulnerable works that reveal the power of art in the psyche and society. Her epic poem weaves a story from childhood in an aristocratic family whose Tartar lineage dates to Genghis Khan and which was shattered by the trauma of World War II to a life of courage that defied confining categories of nationality, materiality, and gender. Her revolutionary and sexually charged Abakans—the only contemporary artworks named for their maker—sparked an international art movement. Determined to engage in a global dialogue, she crossed the Iron Curtain more than any other artist to hold hundreds of exhibitions and went on to become one of the great heroic sculptors of the twentieth century. Her narration offers a uniquely intimate view of an artist’s deepest thoughts and private experiences. Yet more than personal reminiscence, Abakanowicz is driven to share an understanding based on respect for the organic world, reverence for indigenous cultures, and reminders from history. The wisdom gained speaks to no less than the survival of the planet.

See this illustrated timeline of Abakanowicz’s life and work.

BIOGRAPHICAL SUMMARY

Born in 1930 Magdalena Abakanowicz in Falenty and resided throughout her life in Poland. The innocence of childhood was interrupted by the onset of World War II when she was nine. In successive years her family moved to Tczew and Gdynia, where she entered state schools, after having first been educated by a tutor on the family’s estate in her early years. In 1949 she enrolled in the State Higher School of Fine Arts in Gdańsk, based in Sopot, to study textiles. When in 1950 that department was eliminated, she transferred to the Academy of Plastic Arts in Warsaw, graduating in 1954 with a diploma from the Faculty of Painting in the field of textile.

From 1954-56 Abakanowicz worked as a supervisor at the Central Natural Silk Plant “Milanówek,” where she painted organic designs on cloth for production. Starting in this period, too she collaborated with state cooperatives, creating collages that would be translated into unique woven wall works, as well as producing designs for printed fabrics for domestic use. Her works began to be seen in competitions and shows of interior design. By 1955, however, Abakanowicz started to make paintings in oil and gouache alongside her woven works, yet it was the latter that most often seen in exhibitions in Poland. When in 1960 Abakanowicz had first solo show in Warsaw’s Kordegarda gallery, it was her independent paintings that she choose to exhibit.

Fiber continued to be an area of creative experimentation for Abakanowicz. By 1960 she began to weave herself and, without a studio, became a member of the Atelier Expérimental de l’Union des Artistes Polonais in 1961, an informal organization of the pioneering Polish weaver Maria Łaszkiewicz in whose modest basement space was offered looms to aspiring artists. In 1962, thanks to the nomination of Łaszkiewicz, Abakanowicz showed to great acclaim at the 1ère Biennale Internationale de la Tapisserie in Lausanne, Switzerland. By 1964 her bold compositions and avant-garde use of varied fibrous materials led critics to dub her woven Abakans after the artist’s own name, as no existing genre seemed to embrace her radicality. Then, selected among three Polish weavers to show in the prestigious VIII Bienal de São Paulo in Brazil in 1965, Abakanowicz was awarded the gold medal in applied arts. The world opened up for the artist that year. She acquired her first home and studio (where she continued to work until 1989); she made her first permanent public work, welded steel formed as a tree trunk for the 1. Biennale Form Przestrzennych in Elbląg, Poland; and was appointed a professor at State Higher School of Plastic Arts in Poznań, Poland (where she taught until 1990 and which is now named the Magdalena Abakanowicz University of the Arts).

In 1967 Abakanowicz’s weavings became three-dimensional sculptures. While featured in numerous shows, these works were perhaps most powerfully presented, taking on their fullest expression as living entities, in the 1969-70 film Abakany, a collaboration with director Jarosław Brzozowski. In 1970, beginning with her solo show in Södertälje Konsthall in Sweden, she began creating temporary environments composed of Abakans and ropes. This concept continued through the 70s in successive shows in Europe, the UK, and US which were conceived as a total works of art. Public projects also emerged with her audacious Rope in Edinburgh for the Atelier ‘72, a work that threaded throughout the city. This decade, too, saw her first site-specific public commissions. The greatest and only such extant work in its original form and context is Bois le Duc, spanning over twenty-two meters in the Provinciehuis s’Hertogenbosch in the Netherlands.

Yet her sculpture was to transform. In 1973 Abakanowicz initiated her cycle Alterations: Heads (1973-75), Seated Figures (1974-79) and Backs (1976-84). Her material shifted, too, as she chose one already intrinsically carrying its ownhistory. From used burlap sacking she created human-like forms, giving each their own individuality. Her exploration of figures continued as her sculptures multiplied with the series Crowds (1985-2008), Incarnations (1986-2008); and Anonymous Portraits (1985-2008). By 1976 the explorations of media expanded.

Representing Poland at the 1980 Venice Biennale was an astounding international achievement. This unfolding experience opened with a temporary outdoor installation Trzepaki of stitched-together burlap sacks slung over a wooden A-frame; they stood like sentinels in front of the pavilion. Visitors first encountered the artist’s Hand (1976) and a length of rope which led them in as it arrived around the Wheel with Rope (1973). There, for the first time on public view, were the mounds and inner worlds that comprise Embryology (1978-81). Finally, one arrived at the haunting and solemn Backs(1976-80). Had the Golden Lion Award not been suspended that year, Abakanowicz surely would have been a challenger.

Venice introduced her work to collector Giuliano Gori who invited her to work at his sculpture park (Spazi d’Arte at Fattoria di Celle in Pistoia, Italy). There Abakanowicz undertook her first major permanent outdoor installation, Katarsis (1985), which also was her first use of bronze. This launched a distinguished body of public work created for the specific sites and in materials she felt captured the essence of the place: Negev (1987) for Israel Museum, Jerusalem, is seven huge wheels made of local limestone; Space of Dragon (1988), ten enormous, prehistoric-like bronze skulls at Olympic Park in Seoul; forty headless backs, Space of Beclamed Beings (1993), site outside the Hiroshima Museum of Contemporary Art on a hill to which residents fled after the bomb; the twenty-two various-sized concrete ovoids that make up Space of Unknown Growth (1998) in Europos Parkas in Vilnius continue to grow into the landscape; and Nierozpoznani(Unrecognized) (2002) in Park Cytadela in Poznań and Agora (2006) in Grant Park in Chicago, Illinois, are each over 100, gigantic headless cast-iron figures.

Another prominent series of this period was her War Games (1987-95), a total of twenty-one huge forms from discarded tree limbs that are alternatively weapons and ravaged bodies. In 1980s she began to make large-scale drawings, a medium previously employed on a smaller scale, now took on greater significance. Working in this media she deepened themes found in her sculptures with series Bodies (1981), Embryology (1981), Flies (1981), and Wild Flowers (1998-99). Behind all these works, Abakanowicz sought to build a dialogue between the past and present, connecting distant societies who struggled and suffered similar despite coming from different cultures and civilizations.

The artist’s apprehensions about human condition finally led her to a deep concern for the vulnerability for the planet. The relation between culture and nature is expressed in such series as Hoofed Mammal Heads (1989-90), Mutants (1992-2001), Birds (1994-2009), and Coexistence (2002-10). In 1991 the artist, in team with architects Halina Starewicz and Andrzej Pinno, was selected as one of four artists to compete to redesign La Défense district in Paris. Hers was a visionary project of a green-architecture housing estate. Arboreal Architecture took the outward form of trees covered in plants, while inside powered by alternative energy sources, they revealed a host of services essential for good living. Unrealized (in fact, no work was undertaken for this competition), Abakanowicz returned to sculpture, creating the related bronze Hand-Like Trees (1992-2004).

Abakanowicz also considered writing to be one of her mediums. This began with her prose poem Portrait x 20 in 1978 and 1979 with Soft. In 2008 she published her autobiography Fate and Art. Monologue, presenting her story of struggle against circumstances and determination to realize her creative vision (Skira, second edition, 2020). A compiled selection can be found in Magdalena Abakanowicz: Writings and Conversations (Skira, 2022).

Magdalena Abakanowicz’s works have been shown in over two hundreds solo and more than six hundred group exhibitions around the world.The artist suffered from Alzheimer’s in her last years and died in Warsaw on April 20, 2017.